In Vietnam, each house has an altar that ensures the memory of the ancestors over four generations, when it is not to «get in touch» with them.

Ancestors Altar in Binh Thuy old House, Can Tho - © Mr Linh's adventures

Brief introduction to ancestor worship in Vietnam

Ancestor worship, known as tín ngưếng thờ cúng tầ tiên in Vietnam, dates back to the Dong Son culture (1st millennium BC), even to pre-Dong Son culture. The original foundation of the Vietnamese national community, it represents a factor of uniqueness, family and social cohesion, for a people that has managed over its long history to reconcile a wide spectrum of religious, philosophical, cultural and political influences.

This practice of veneration of ancestors through worship by their descendants is not specific to East Asia since it is also found in some countries of Africa and South America. Whatever the latitude, ancestor worship refers to the unity of the clan, the family, thanks to its cohesion on the mother earth and the harvests she can produce.

The cult of ancestors in Vietnam, a brief historical overview

Ancestor worship is based on the belief that the soul of a deceased survives after death and that it then gives itself the mission to protect its descendants, but also to reprimand them if necessary. There is therefore no separation between the world of the living and that of the dead, the two being interconnected by a set of consciousness, symbols and rituals.

Dang Nghiem Van, a Vietnamese specialist on religions, supports the idea that every nation has a national religion, regardless of the foreign traditions that have been grafted and assimilated. Thus, ancestor worship is very often associated with Buddhist beliefs, Taoist practices or Confucian doctrine. Even though this ancestral cult existed long before all these precepts appeared. It is concluded that ancestor worship is the national religion of Dragon Land. And then, a thousand years of Chinese colonization and the influences of India – via Buddhism – infused into Vietnamese culture this fidelity to the Blood, this invisible link that connects the Earth to Heaven.

Note that worship is here used in the wide sense: the ritual of ancestor worship can be addressed at the state level, with its men of honor and virtue (we think here especially of the Hung kings). It can be practiced towards the village, with its tutelary geniuses and virtuous inhabitants who have worked for its prosperity and security. And finally, ancestor worship can be practiced at a third level, that of the family and its deceased ancestors.

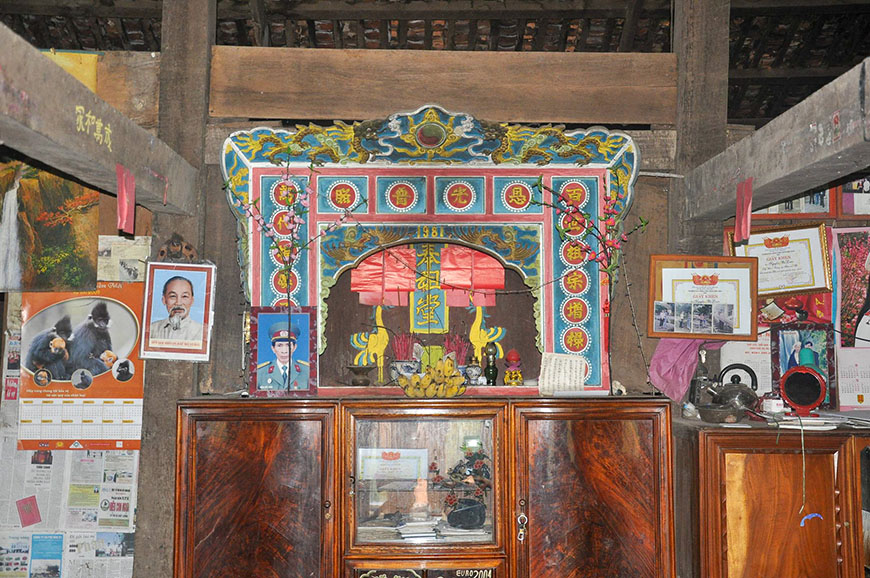

Old altar in a traditional house, North Vietnam - © Mr Linh's adventure

The cult of ancestors, an ethic

The cult of ancestors is an ethic, a duty above all. But make no mistake: we can only grasp Vietnamese culture and therefore the family, social, national hierarchy, by perceiving the world according to the traditional popular beliefs of the Vietnamese. In particular that there is a constant interaction between the visible world and the invisible world. It is necessary to see the earth as being populated by individuals in flesh and blood, more or less alive, also hosting gods and geniuses, benevolent spirits (of which the ancestors are part) or on the contrary evil, which one will take care to dread. During your next adventure in Vietnam, you will not fail to notice a special altar, placed on the ground, on which rest offerings and incense, in honor of the genius of the shop, restaurant, workshop… It is not a profession that does not have its tutelary genius. One should not confuse it with the altar of the ancestors, located, as for it, always at the highest point of the house.

The cult of ancestors, an element of family cohesion

To venerate the ancestors, the members of the family, is to show respect, an attachment, a gratitude towards our elders, as we testified to them during their lifetime and as they themselves testified to their loved ones. A family, a clan, is united by the intergenerational bond of filial piety. This link is found on the other side in the ritual of ancestor worship. We are here more about practices than beliefs. Or to be more precise, on a set of beliefs materializing by ritual practices - birthdays, funeral rites, mourning rites, marriage – of which of course the cult of ancestors is part. In addition, it must be kept in mind that by this set of beliefs and ritual practices, each individual is linked not only to members of a family still alive but also to deceased ancestors. In fact these many rituals and ceremonies are factors of family cohesion, but also social and national. Perhaps even with an initiatory dimension that we will leave here to scholars the leisure debate.

Shortly, let’s say that the Vietnamese family structure is shaped in a clan way, following a patriarchal pattern and a patrilineal kinship system. In other words, all descendants of a common ancestor of at most 4 generation ago, belong to the same clan (ho, or toc, in Vietnamese). All members of the clan have the same surname. The leader of the ho is the elder; he is the one who holds the authority over the whole clan, working for the cohesion between all the members. Not to mention that he is also responsible for respecting the worship of ancestors and the maintenance of graves. As such, he is the guardian of the gia pha, this genealogical register that is somehow the written memory of the clan and its members.

The cult of ancestors today

|

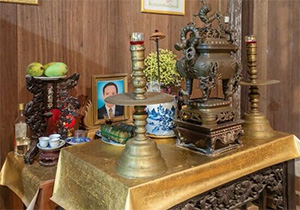

| Altar in Cai Be, south Vietnam - © Mr Linh's adventures |

Despite the modernization, ho is still the reference family structure and especially for all that is identification of ancestors.

However, the contemporary period sees a clear evolution, where individualism takes an increasingly prominent place, without however moving away from the

cult of ancestors. However, our modern times are increasingly moving away from the notion of clan to the benefit of the Gia, that is, families that gather the next of kin under one roof. So we see nowadays the authority exercised by the head of the family (Gia Trung), the authority of the head of clan becoming more and more symbolic. On the other hand, the latter remains the faithful guardian of the

cult of the ancestors.

More prosaically, the

cult of ancestors is recognized by the Family Code (1995), which reviews that during a succession, a part of the family heritage must be reserved for cultural property and can therefore not be shared.

And finally, how not to mention the Lunar New Year’s Tet? Every year, it is the same frenzy, even the same fervour, in the preparation of the arrival of the first day of the new year. Regardless of social class or religious affiliation, everyone will decorate their house with plum blossoms to chase evil spirits, cook the famous (and delicious) Banh Chung (a sticky rice cake, stuffed with meat)… And then comes the big evening where each family meets in the main room of the house. Bowing down several times before the altar, the householder summons the deceased to participate in the festivities in the company of the living. The supernatural joins the daily, the sacred meets the profane.

Finally, know that the festivities organized for the first birthday of a child always begin with

worship of ancestors. Similarly, child marriage – a symbol of continuity of family lineage and worship – also requires very strict observance of specific rituals, including sharing the good news with ancestors.

►

Discover Tet of Lunar New Year in the 3 regions of Vietnam

The cult of ancestors, essence of Vietnamese culture

Despite invasions, colonizations, wars, the spectacular economic boom of this country with a Marxist-Leninist tendency, the heart of Vietnam continues to beat at the rhythm of ancestral rites, millennial beliefs feeding on multiple external influences. This ancient vibration is expressed in three states:

- Spiritual, in its preparation for life beyond,

- Biological, based on generational renewal

- Social, in its regular social practices, notably through ceremonies and rites.

We cannot deny the evolution of society, especially with this tendency to want to copy the customs of Western countries without passing them through the filter of discernment. Can this evolution harm the cult of ancestors? Paradoxically, the rituals of ancestor worship help maintain traditional Vietnamese morality by recalling the facts and merits of the ancestors. Some scholars have even talked about antidote to an ethnocide more or less real. In this world torn between globalization and return to the roots, between greed and ecological awareness, will the millennial tradition be forever the ultimate salvation?